A Course in Perception

by Jeremy Wilkerson

Our brains manipulate us by lying to us about the outside world. This course will teach you to separate fact from fiction in the information that reaches your consciousness, so you will no longer be a slave to your biology and conditioning. It should take about 15 minutes to complete it. It will start by laying out a theoretical framework, but an intellectual understanding isn't enough. You can gain a true understanding only by experience, so the initial theoretical explanation will be followed by practical exercises that will help you to understand your own mind and perceptions.

Theory/background

Our conscious experience is that we seem to sense the world directly, to be directly aware of the world around us, but that is an illusion. The information that is collected by our senses undergoes significant processing and transformation in the brain before reaching our conscious awareness. This is necessary, because we wouldn't be able to make sense of the raw information collected by our sense organs (retinas, cochlea, touch receptors, etc.). Visual information, for example, goes through many levels of processing at different locations, starting in the retina: edges are detected, color is determined despite varying illumination, distances are determined (depth), individual objects are separated, motion is detected, spatial relationships are determined, object identity is determined, and, in the case of faces, personal identity is determined. Auditory information likewise goes through multiple processing steps before we can ultimately identify a familiar sound or recognize a spoken word.

At each processing step the brain adds calculated or derived information to the sensory stream. For example, information about object boundaries is added to the visual stream, as well as depth, color, movement, and so on. We will refer to this added information as annotations. The annotations are not part of the raw sensory information that is received by our sense organs; they are added later by the brain, which is a key point. The annotations are "mixed in" with the sensory information, so that they seem to be an integral part of it. Our conscious experience is that the annotations seem to be a part of the sensory information, and we may not realize that they are added after sensation. The sensory information and annotations together form a perceptual stream, and we accept that stream as reality. Many of the annotations, such as those mentioned, are objective and help us to understand the world around us, but there are some that are more opinion than fact. An example of an annotation that is opinion is the "cuteness" of a baby. Cuteness isn't a property that babies possess; it's a label or annotation assigned by our brains, with the biological purpose of getting us to take care of them. Other opinion-based annotations will be discussed later. The purpose of this course is awareness of the perceptual annotations, so we can think critically about those that are opinion, as opposed to accepting them as fact and being driven by them.

Exercises

These exercises are intended to help you become aware of your perceptual annotations, so you can view them objectively. We will focus on visual perception, but the same ideas can be applied to auditory perception. To some extent the annotations form a hierarchy, with later annotations building on those before.

Exercise 1

Close one eye and hold your arms extended in front of you, with your index fingers pointed toward each other and your other fingers curled. Move your arms together so that your two index fingers touch each other on the tips. It's difficult with one eye closed. Try again with both eyes open, and it should be much easier. Sight with two eyes (stereoscopic vision), gives the brain information it can use to calculate depths (distance from you to an object). Try to see the difference in how your hands "look" with both eyes open versus with one eye closed. There isn't a significant change in color, shade, shape, or any other purely visual property. The difference is the presence or absence of the depth annotation.

Exercise 2

Continuing on the previous exercise, go somewhere that you can see objects at various distances from you, such as some within a few feet, some several feet away, and some further away. Most indoor locations will be adequate. Close one eye and see how the scene looks, then look with both eyes open. Repeat this, looking with one eye then looking with both eyes, until you can see the difference. The difference is subtle but definite. With one eye closed the scene should seem relatively flat. With both eyes open there is depth information (annotations) mixed into the perceptual stream. With practice you should be able to recognize the difference.

This depth information isn't part of the sensory information but is calculated by the brain based on the difference between what your two eyes see. It then gets mixed in with the sensory information so that it seems to be part of it. The room "looks" different with both eyes open because of the depth annotations.

In addition to stereoscopic vision, the brain can also determine depth using visual perspective, which has to do with how the position of objects relative to us changes their apparent shape. An example is how the edges of a straight road seem to get closer together in the far distance. The next exercise explores this further.

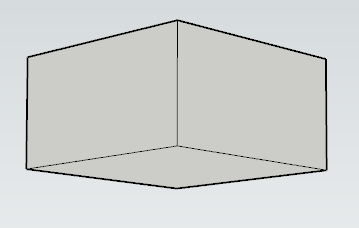

Exercise 3

What do you see in the figure below? Does it look like a box or a room? Depending on how your brain assigns depth annotations it can look like the sides and bottom of a box, or like the floor and two walls of a room. It is obviously a flat image in reality, but your brain uses perspective cues, such as line angles, to calculate depth information then adds it to your visual stream as annotations. Try to switch between the two perspectives at will: seeing it as a room or as a box. It "looks" different when you are seeing it as a room versus seeing it as a box, though clearly nothing has changed in the raw sensory information that is being received by your retinas. Can you also see it as simply a flat image with an assortment of line segments? If so it will look different to you again. This exercise further illustrates how additional information (annotations) gets mixed into your perceptual streams. It also shows that when you are aware of the annotations, you can exert some control over them.

Exercise 4

Look at the following image, which flips every 5 seconds. When it's right-side up your brain will attach an annotation that means "this is a car". When it's upside-down the annotation will be absent, or at lease weaker. You could probably still determine that it's a car, but it doesn't have the same kind of strong annotation when it's upside-down. In other words, it doesn't look as much like a car. Try to recogize the "car identity" annotation, by seeing the difference between how it looks when it's upside-down vs right-side up. Object identity is a strong type of annotation, and it's very important in helping us make sense of the world around us.

"Mitsubishi Lancer 1600 GSR Rally Car 1974" by mark_irvine is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

The human face holds a special place in perceptual processing. There is a relatively large region of the brain that seems to be dedicated solely to recognizing faces1. This explains our ability to identify people based on facial appearance, when differences can often be quite small. The importance of facial recognition also explains our tendency to see faces where there aren't any. The next exercise explores the perception of a face.

Exercise 5

Look at the animated image below. You will probably recognize it as similar to a face or emoji, at least during a portion of its rotation. There will probably be a portion of the rotation where it doesn't look to you like a face, such as when it is upside down, and a portion when it does look like a face. Notice the change when your brain applies an annotation that says "this is a face". Try to get a feel for the difference in how the image looks when the face annotation is present compared to when it is absent. If you always see it as a face, make an effort to see it as geometric shapes and not a face. That should be relatively easy when it is upside-down or close to it, but when it is close to upright your brain will likely annotate it as a face despite your effort to prevent it.

Some perceptual annotations have emotional value, but like the annotations discussed previously, they are mixed in with the perceptual stream and seem to be part of it. We tend not to realize that they are akin to opinions produced by the brain and are not part of the external world -- not part of the information our sensory organs receive.

Exercise 6

Look at the following scenery image. You will likely find it to be beautiful. If not, find an image that you do see as beautiful. What is this "beautiful" quality? It isn't a color or a shape. It isn't part of the color of the trees or the color of the sky. It isn't the shape or form of any object or shadow. Strictly speaking it isn't a visual property, yet it changes how the image looks to you. You might say that the image "looks beautiful". Beauty is an annotation. Your brain decided, for whatever reason, that the beauty annotation applied, then it mixed it into your visual perceptual stream. The result it that the sense of beauty is a part of your visual experience of this image. It's almost like a glow.

Try to modify the beauty annotation by changing your thoughts about the image. Tell yourself it's a cold day and you would be uncomfortable. There are dangerous animals lurking in the trees, and annoying biting insects. Notice the decaying wood in the water. After thinking these things, does the image look less beautiful, less inviting? Is the glow diminished?

"Mountains of Five Flowered Lake" by Augapfel is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Exercise 7

Look at the following image of a house. It might look scary or spooky to you. Like with the beauty seen in the previous exercise, this scary quality isn't actually part of the image; it isn't strictly visual. Your brain decided to attach a fear annotation to this image, and the annotation was added to the visual stream. The result is that the image "looks scary" to you. The fear annotation serves a useful purpose, which is to make us avoid potentially dangerous situations.

Again, try to alter the annotations by changing your thoughts about the image. Realize that part of the reason it looks spooky is because it's in black-and-white. Notice that it is an old house that was probably beautiful at one time. Now it has broken windows, missing roof tiles, other signs of age and wear, and an over-grown yard, all of which contribute to the eerie feeling. The trees might be pretty if you saw them in color. Does the image look less scary now?

"Spooky House" by tomt6788 is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 .

Exercise 8

Look at the following photo. Most people would say the woman in the photo is beautiful. when viewing a person the brain's annotations are stronger. Our sense of attractiveness in other people evolved to give an indication of a person's health and fitness. We can even tell a lot about a person's mentality from the appearance of their face.

Try to be aware of the sense of beauty with this photo. It is different than the purely visual aspects, such as color and form, yet it seems to be part of the image, because your brain mixes the beauty annotation into the visual stream.

You might not be able to see this image without the sense of beauty, but try to at least lessen it by how you think about the image. She's in an awkward position, and she must be uncomfortable, with the way her neck is bent. The way the light reflects off her skin and clothes produces a literal glow that adds to the perceived glow of the beauty annotation. The slightly reddish color of her cheeks adds to the sense of beauty, because your brain sees it as a sign of arousal. Her eyes are striking, with their dark color and light speckles, and they are accentuated by eyeliner. She appears to be looking at you, because she's looking at the camera. These thoughts may or may not have diminished your sense of beauty in this image, but you can at least be aware of the beauty annotation.

"beautiful faces" by tommerton2010 is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Exercise 9

Look at the photo below. Does the man appear threatening? To many people he will. Most people have a tendency to find black men threatening2, for cultural reasons. Countless messages of various kinds have taught us that black men are dangerous. The sense of threat may appear to be part of the image but it is added by the brain. The fear annotation often serves to keep us safe, but in this case it goes too far. One need not fear black men in general.

Try to alter the annotation by telling yourself that you don't have a good reason to fear this man. He's just a man. Try to see his expression as sad or calm rather than angry. That shirt looks like it could be a work uniform. Perhaps he just got off work and he's tired. His bloodshot eyes are likely a sign of allergies or dryness, and they're probably uncomfortable. You may not feel like smiling either if your eyes were like that. Does he look less threatening now?

"Man" by Terrie Schweitzer is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 .

Hopefully these exercises have taught you about separating the facts in your senses from the perceptual information that the brain adds. As you go about your life, try to be aware of the extra information your brain adds to your sensory streams, which is often emotional in nature. Sometimes this information is helpful and sometimes it isn't, but it's important to recognize it for what it is rather than accepting it as fact. This means being skeptical about what your brain is telling you. It can be very hard to separate fact from fiction in our sensory streams, which means separating sensation from perception. But it's the only way to see the world as it really is.

The perceptual information created by our brains is especially strong when we see (or hear) other people. With an effort we can get past our perceptions -- our preconceived notions -- and see people as they really are. By doing so we open up a new way to relate to others.

Getting past perception and judgment and seeing the world and others as they really are allows one to be fully aware of the present moment, which is like stepping into a brand new, amazing world.

In the wise words of Eckhart Tolle, "When you no longer perceive the world as hostile, there is no more fear, and when there is no more fear, you think, speak and act differently."

Feel free to contact me with any comments or questions: jeremy@talkingape.org

References

1. Kanwisher, N., McDermott, J., & Chun, M.M. (1997). The fusiform face area: A module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. Journal of Neuroscience, 17, 4302-4311.

2. Brian A. Nosek, Frederick L. Smyth, Jeffrey J. Hansen, Thierry Devos, Nicole M. Lindner, Kate A. Ranganath, Colin Tucker Smith, Kristina R. Olson, Dolly Chugh, Anthony G. Greenwald & Mahzarin R. Banaji (2007) Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes, European Review of Social Psychology, 18:1, 36-88, DOI: 10.1080/10463280701489053